Photo © AntonioGravante | Deposit Photos

This post was inspired by the book Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft, which discusses the misinterpreted advice in a fairly detailed way that made me want to take notes.

If you’ve made the usual rounds of writing advice, especially in Writer’s Digest, you’ll have seen a laundry list of advice. It’ll be in the form of a top ten list, like the silly kill your darlings. There’s one that’s on every list, and it leaves a lot of writers struggling to understand it:

Show, not tell.

MasterClass describes it as “simple” advice, and that’s not true. It’s actually an advanced level writing skill that someone—probably in the 1990s—tried to simplify for the new writer starting their first novel. Might have been an agent after seeing manuscripts come into the slush piles and immediately getting form rejections.

Of course, it sounds easy to explain, and everyone adapted it. Even what the MasterClass article describes is NOT easy at all. I’ve been reading old The Writer Magazine issues, from the 1940s and 1950s. They describe elements of it (though the phrase “Show not tell” is never mentioned, so it definitely came later), and sometimes I have to reread it to check my understanding. Often, one element is implied, I think, because they assume you already know. In recent years, it gets too simplified.

It’s characterization.

How else can you explain why a writer would think that showing a character being angry is shaking a fist without addressing characterization at all?

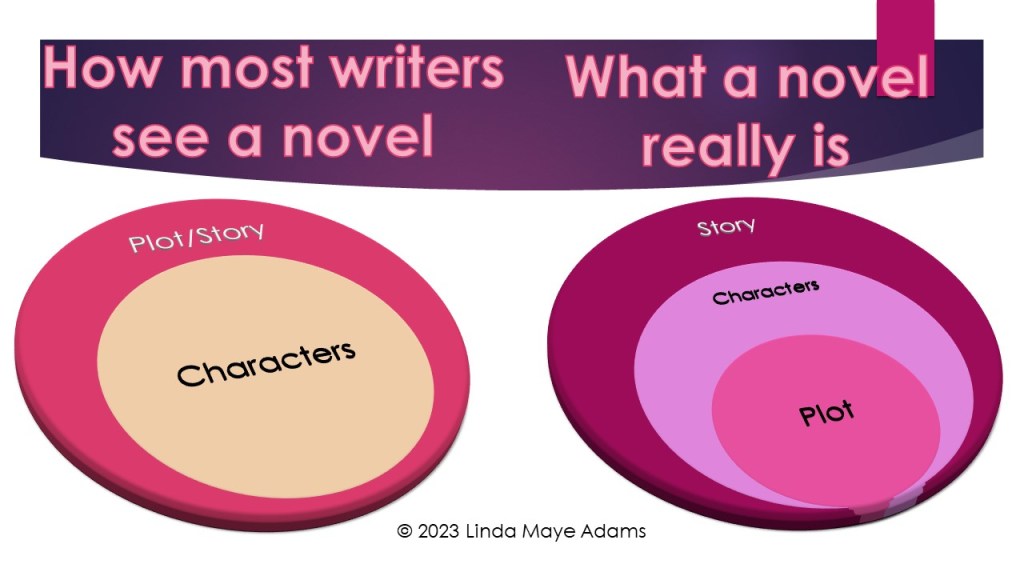

The problem starts here, with how writers think of a novel versus reality:

The left Venn diagram originates with all the craft books because it’s easy to teach plot. So much so that many writers use plot and story interchangeably, though they are two different elements. Often, you’ll hear writers ask, “Are you plot-focused or character-focused?”

Well, without characters, plot is pretty meaningless. Story is the overall umbrella, encompassing characters next, and everything else—plot, setting, description, dialogue, theme—is through the character’s eyes.

So if your character is only getting angry by waving his fist, it’s barely hitting superficial “showing”, and is a false detail. Your character being angry is a whole story action. What led up to it in the previous scenes? Does he have any traits that you need to bring in earlier that would contribute to it? (i.e., he gets angry when he’s frustrated.) What did one of the other characters do, or not do? What is his reaction after the angry scene? What is the impact of it in the scenes following?

Then there’s the setting and the five senses. This character who is angry is interacting with a setting and experiencing the five senses in some way. In the book Dogged by Death, an off-page character is so angry at being fired that she gets in her car and loses connection to the world around her. She hits a dog and doesn’t even notice (the dog had a broken leg and was okay). For this, the main character is a veterinarian. A minor character runs in to tell her about the dog, and they run out to help the dog. And they’re all having different reactions to what just happened.

There are lots of little ways to do this:

- Word choices that evoke an emotional reaction (study Nora Roberts; she does this really well)

- Rhetorical devices (these are fun to play with).

- Metaphors

- Specific details (which will use the five senses), and details that communicate judgment or opinions (this is from the book I mentioned at the top of the post).

There are also lots of big ways to do this:

- The reaction of other characters, even ones who may not be present. If your character has a big blow-up with her boyfriend, her best friend might call the guy a rat, a parent might think the character overreacted, and another might think she needs to bang another guy.

- Your angry character enters the next scene and reacts to what just happened. Or it could take several scenes to work through the reaction. Jack Bickham talks about action and reaction in Scene and Structure (also an advanced skill).

- A later scene could present an unexpected plot event caused by the character’s original angry reaction.

And it’s not easy to do. Characterization itself is often reduced to character worksheets because that’s similar to outlining. You could spend years learning about characterization and always find something new.

Worse, everyone tends to think only about the scene that needs the reaction. If the reader has gotten that far, they may not buy into the angry scene if no groundwork has been laid with the characterization prior. It’ll feel like it dropped in from the sky from nowhere.

Show versus tell is something that starts at the first line of the story and continues throughout, tangling itself into everything.

I love the dogs; they remind me of Chet and Trixie (Chet and Bernie mystery series).

LikeLike

Btw, Working Writer (I subscribe) is a good writing newsletter with lots of helpful advice :

Working Writer

http://www.workingwriter1.com

Published bi-monthly, Working Writer is filled with articles on writing, promotion, freelancing, publishing, different genres, how-to, and how-not-to. WW offers ..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Pagdan! I’m checking it out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve had to learn that “show, don’t tell” has limits – which I’ve only ever heard one writer talk about, and that was in a description workshop at a convention years ago.

The writer (John D. Brown) put an image on the screen of a shirtless man with very impressive, possibly tribal, tattoos. The man was in profile, and he was holding a baby. The tattoos framed the baby in a way that the photographer in me envied.

He then said, “I defy anyone to describe that in detail in a way that actually conveys this picture. The best you can do is evoke an image.”

So that’s the first limit: not everything can be “shown” in words.

I’ve never heard anyone talk about the second limit, except one friend and I during the process of de-programming ourselves from a certain writer’s message board.

The second limit is that, broadly speaking, the more words you devote to something, the more weight it carries in the reader’s mind.

The problem is that not everything in a story carries equal weight, and therefore not everything needs a lot of verbiage devoted to it.

Without that acknowledgment, “show, don’t tell” is…well, not meaningless, but certainly not helpful.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So true, Peggy on the first one. Sometimes you don’t need a lot of detail to convey the emotions and feelings about what you’re describing…just the right words. I’ve seen writers try to control the picture the reader sees, much like a movie, and it’s dull!

On the second, I have seen it discussed once and may still be available. Holly Lisle discussed it as part of her revision process in How to Revise Your Novel (it’s still available, but I took it in 2010, so it may have changed). She’d had a character readers bonded to and she hadn’t intended to do anything more than a few scenes. So she had a points system to make sure it wasn’t overbalancing. If the character had a first name, one point,; last name, another point; title, another point; and so on. Me–if the character is just window dressing (the extra in the background), he gets mentioned (i.e. tourist), but nothing more. If he interacts briefing with the main character, he gets one descriptive detail. If he’s going to have some involvement coming up, he’ll get more commentary. And if the’s going to be important in the story, he’ll get about 3 descriptive elements, and then I bring in more and start tagging him.

LikeLiked by 1 person